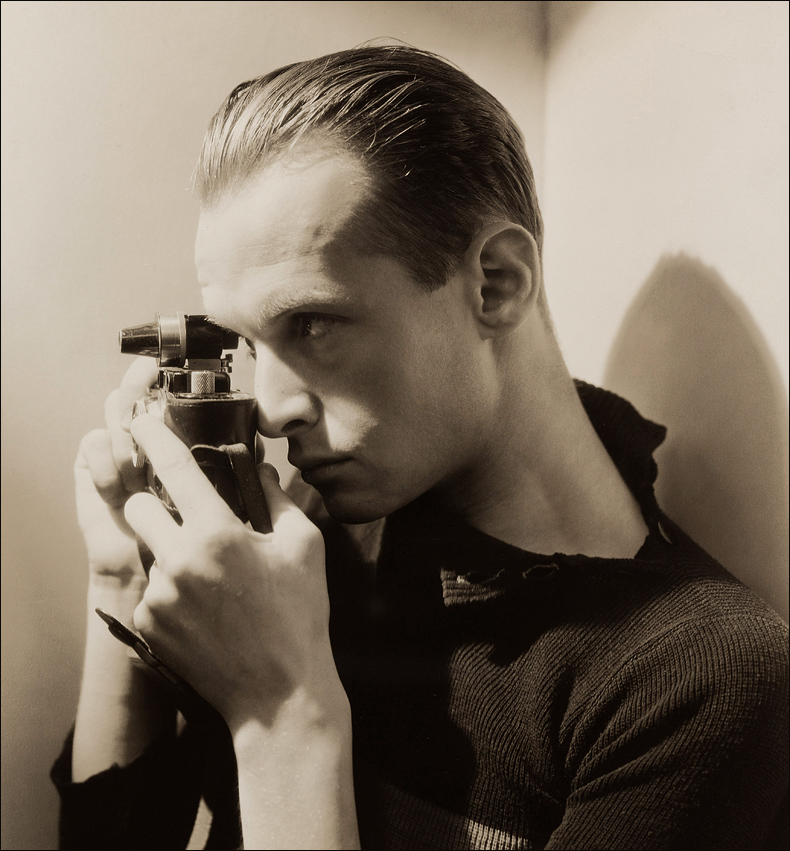

Henri Cartier Bresson by George Hoyningen-Huene, NYC 1935

© George Hoyningen-Huene, © Horst

courtesy Staley-Wise Gallery, New York

The Henri Cartier Bresson exposition is epic: three hundred works plus paintings, drawings and letters. There are also quite a few snaps of ‘HCB’, film of him working and clips from films in which he acted. Before he took up the photograph, Cartier-Bresson tried several métiers and some of his efforts prove amusing. (There’s even footage of him as Jean Renoir’s clapper-boy).

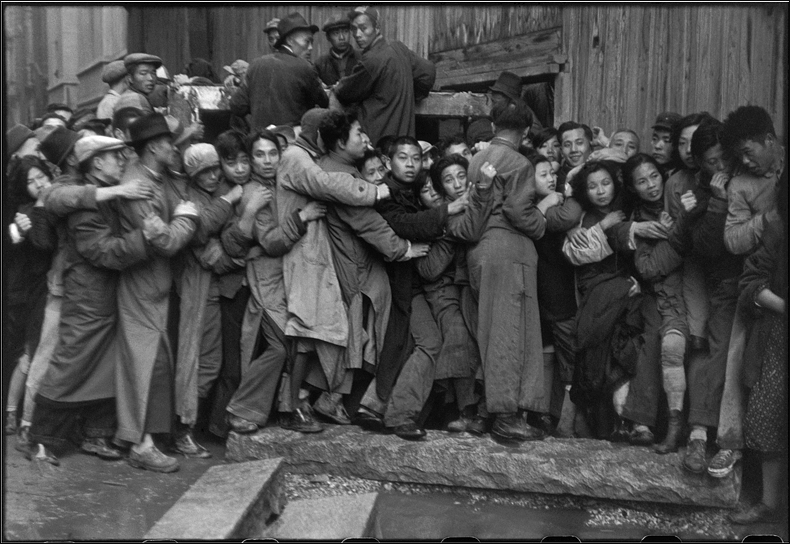

Of course, it’s his photographs that became iconic; most critics here are calling him ‘the Eye of the Century’. That’s not least because he was around when it counted. On show are amazing shots from the Spanish Civil War, in Cuba after the missile crisis and in Russia after Stalin died. He was even in China when the Kuomintang fell to the Communists.*

Crowd in front of a bank as the Kuomintang falls

China, Dec 1948 © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

courtesy Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

Certainly, Cartier-Bresson took politics seriously. Although his engagement altered with time, it remained both a driving force and an anchor. Initially an anti-Colonialist, then a fervent anti-Fascist, much of his early work was also done for the communist press. Yet he definitely preferred observation to theory.

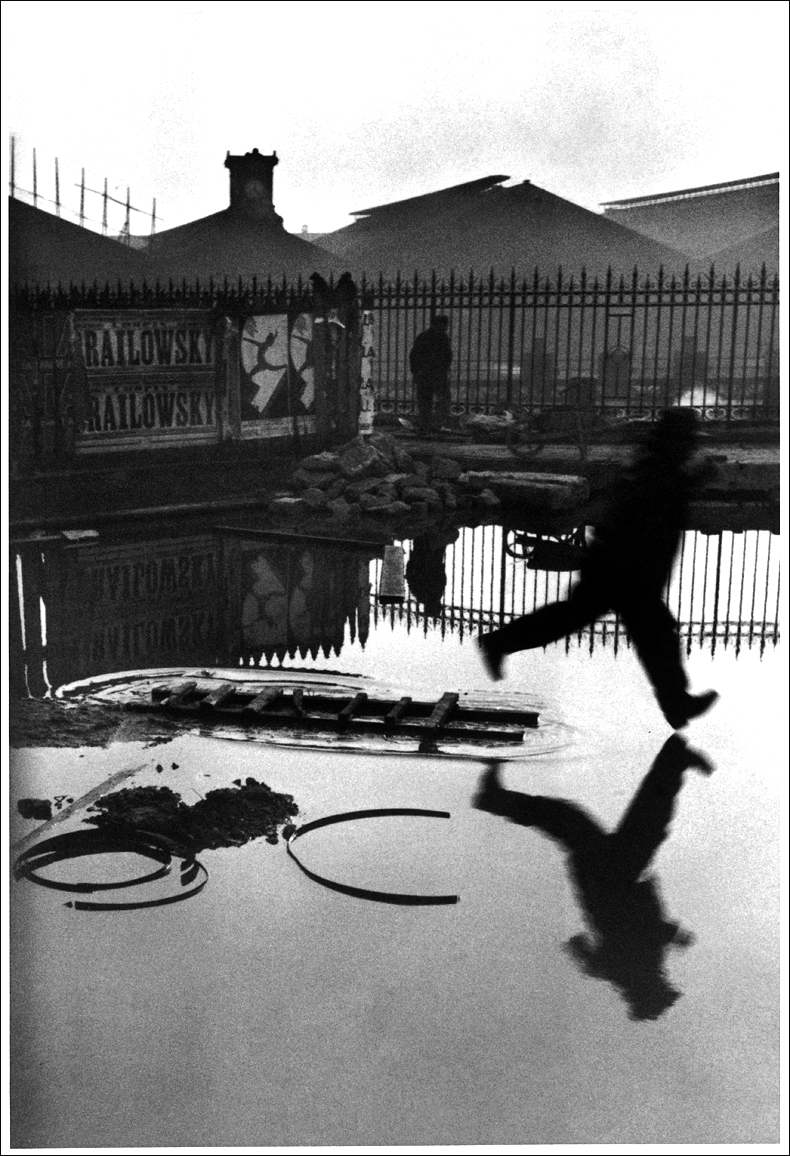

Behind Gare St Lazare, 1932 © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

courtesy Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

Cartier-Bresson was also an artist profoundly changed by World War II. Having started out as a well-off kid with plenty of time for art, he worked and partied – hard – with the Paris Surrealists. He would display a Surrealist point-of-view for the rest of his life.

But during the war HCB spent three years as a prisoner. After the camps, his approach was different…and it went much deeper. In co-launching Magnum, the legendary photo agency, he and Robert Capa, George Rodger and “Chim” Seymour fully intended to remake photography.

His retrospective is mobbed, with viewers snapping away on smartphones. So it may be hard to grasp the revolution these shots once were. Yet it’s clear HCB elevates every moment he grabs. The evidence here may prove Cartier Bresson’s paintings were terrible, yet his photos have a great painter’s eye for composition.

His first book’s English title was The Decisive Moment, a concept that became the cliché about Cartier-Bresson. Yet his original French phrase, Images à la Sauvette (“Images on the Run”), seems more exact. What’s so compelling is how his eye takes in life – how he finds strange, formal, beauties in the moment. Much about all of it comes from his own Surrealism.

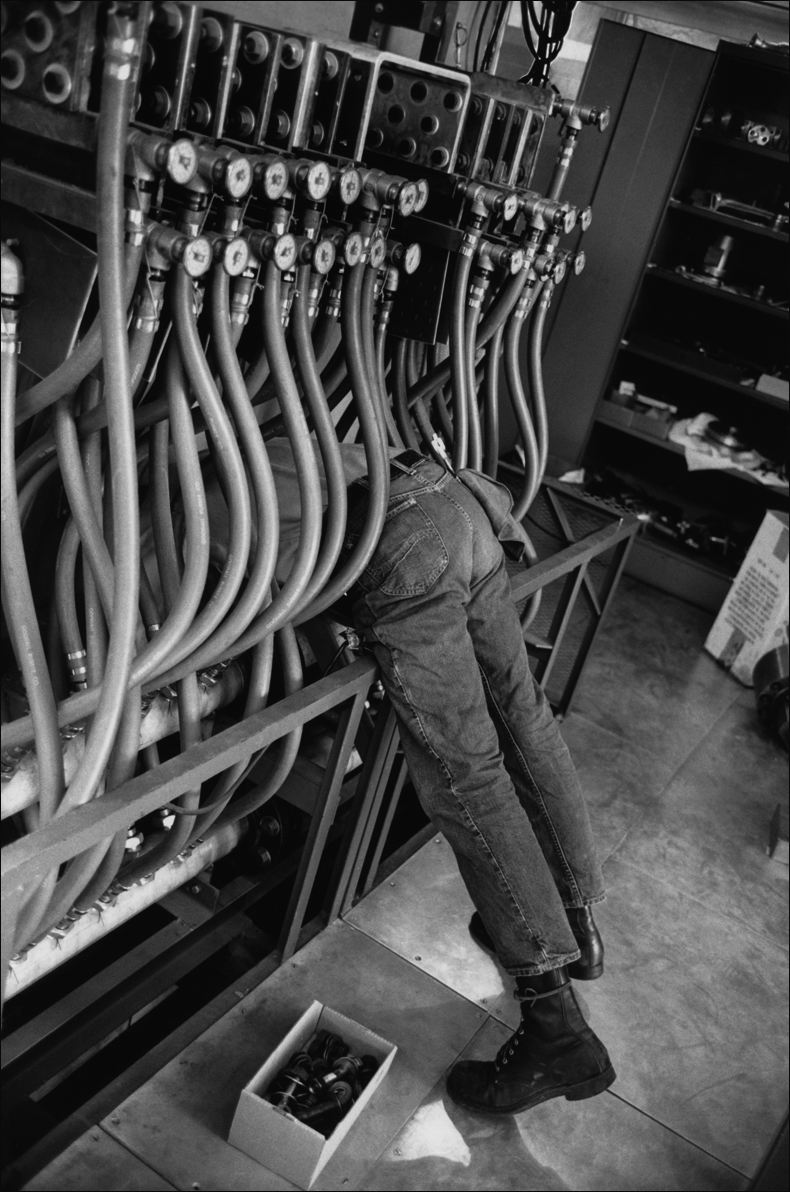

Linear accelerator, Stanford, 1967 © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

courtesy Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

One can relate immediately to the pictures’ humanity. But what Cartier-Bresson does is much bigger than that. His marriage of rhythm and surprise turns seeing into poetry. Is he really the eye of the century? It would be hard to disagree.

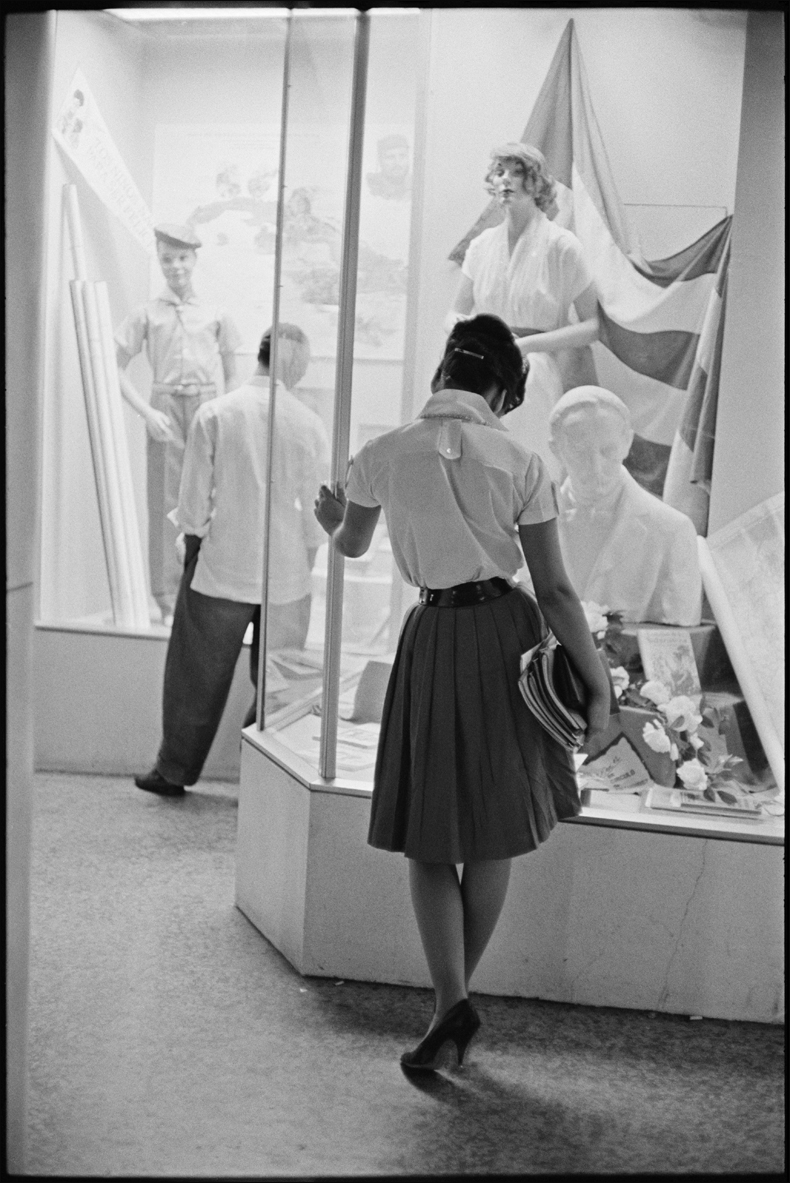

Vélodrome d’Hiver, 1957 © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

courtesy Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

Henri Cartier Bresson runs through 9 June at the Centre Georges Pompidou. With rarities from every era and across the world, the exposition catalogue, Henri Cartier-Bresson (French Edition), is magnificent.

• Cartier-Bresson discusses his work in English. The interview is great and so are the pictures.

* Legendarily, just hours after Cartier-Bresson met Ghandi, the leader was assassinated.